Somewhere in the UK, at this exact moment, a 16-year-old student is trying to memorise all the facts to an essay. This essay will produce a standardised answer, which will help them receive an above average grade. They are not trying to enquire, or imagine, or contradict. They are trying to regurgitate.

What value is there in such a limited use of a human brain, arguably the most complex thing in the known universe? The answer we arrive at is that there has never been any value in students being able to replicate standardised answers – except one. It is an easier way to measure them.

It is not the fault of the student, or the teacher, or the school. It is what happens when you implement an education system that encourages learning with the end in mind. No sense of curiosity. Just a body of text, with the key points covered.

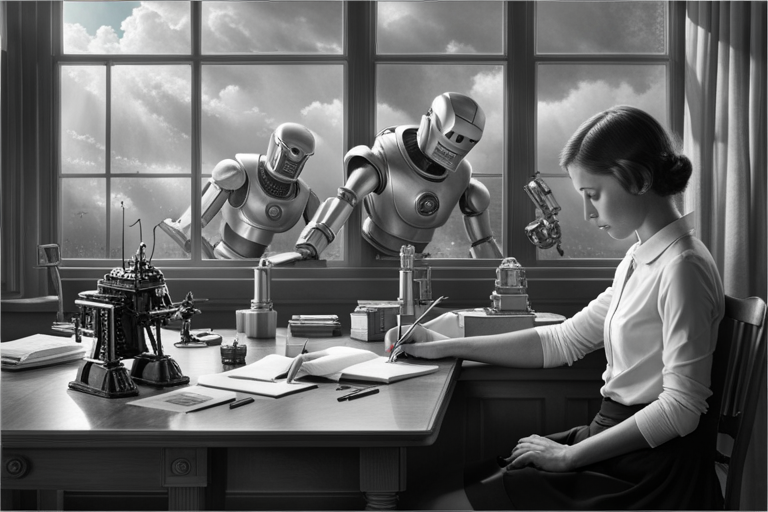

The deepening problem we have now though is that simple, accessible AI tools are able to create these pieces of work in a matter of seconds with simple prompts and a few clicks. And the results are outstanding.

"Wonder is the source of our desire for knowledge"

Aristotle

Of course, there can be incredible benefits to the creation of an essay – deep research, driven by emotion and intuition, new thoughts and reflections created through the synthesis of the material. But those are not the feelings our typical student will be having whilst they revise today.

What we have known for some time is that the type of intelligence that standardised tests are designed to measure is incredibly narrow. Yet paradoxically, it is exactly this type of intelligence that AI is most capable of emulating and overtaking.

And the answers, the essays, the writing that AI is doing so well at academic level is, of course, creating an existential threat to many kinds of jobs.

Over the decades, the inevitable rise of automation has hit the most vulnerable in society hardest. Rural and manual employment has changed beyond recognition. AI now has its sights set on the office. A huge swathe of white-collar jobs is about to be culled with the same unstoppable certainty.

Current predictions show that the job sectors that will see the most growth are inevitably ones in which computer usage is high, such as data analysis and software development. AI will leave us with fewer job roles for a more specialised workforce.

Education, perhaps unhelpfully, has always been linked to employment, so clearly STEM subjects will enable more students to stay competitive in this narrowing job market. But is that all we want our children to study? As employment narrows, do we want the same narrowing of education for our children? And if a large part of the workforce is likely to disappear, should the point of education become something else?

"AI does not understand itself. Humans can."

The answer may not lie in trying to replicate what can now be easily accomplished by an app, but in intelligences that AI does not have. Meta-intelligences.

AI might find many challenging tasks easy compared us, but there is a critical difference, as put forward by Professor Rose Luckin – “‘AI does not understand itself, humans can.”

Luckin has defined a number of meta-intelligences – meta-knowing, meta-cognitive, meta-subjective, meta-contextual, and perceived self-efficacy. These are among the intelligences of the future – at least for now, AI-proof – and the ones education could be focused on.

These meta-intelligences include realising that knowledge is relative and something we construct; understanding what we know accurately and what we don’t; understanding social and emotional intelligence; understanding context and environment; understanding what goals we should be setting ourselves, how likely we are to be able to achieve them, and how can we be effective in the world?

And in the same way that calculators have not removed the need for basic mathematical skills and understanding, neither will artificial intelligence remove the processes that underpin critical thought.

“We must develop the types of thinking that can hold power to account and forge a society where human and environmental needs are met.”

Imagine how much our students could achieve if they are given active techniques to use throughout their lives. Enabling their curiosity, their independent research, and their learning through experimentation, both physical and cerebral. Encouraging their free associations and their trains of thought. Helping them understand how they link new ideas to formed memories, how to self-reflect, and how to collaborate.

It may be that these skills are not as easily measurable, but that should not diminish their greater value.

These are the intelligences we should be focusing on. Not sitting in a bedroom somewhere trying to remember the key phrases that might drive an above average grade and be long forgotten by the end of the summer.

These are the types of thinking that can still hold power to account and help guide us to a society where our human and environmental needs are met.

We should have been basing our education system on these principles for a long time. The irony is that we needed AI to make us aware of it.